4.1 JavaScript language quick start

Author: Goodness, Created: 2019-04-26 11:46:12, Updated: 2019-04-27 11:53:43Background

This section gives a little background on JavaScript to help you understand why it is the way it is.

JavaScript Versus ECMAScript

ECMAScript is the official name for JavaScript. A new name became necessary because there is a trademark on JavaScript (held originally by Sun, now by Oracle). At the moment, Mozilla is one of the few companies allowed to officially use the name JavaScript because it received a license long ago. For common usage, these rules apply:

- JavaScript means the programming language.

- ECMAScript is the name used by the language specification. Therefore, whenever referring to versions of the language, people say ECMAScript. The current version of JavaScript is ECMAScript 5; ECMAScript 6 is currently being developed.

Influences and Nature of the Language

JavaScript’s creator, Brendan Eich, had no choice but to create the language very quickly (or other, worse technologies would have been adopted by Netscape). He borrowed from several programming languages: Java (syntax, primitive values versus objects), Scheme and AWK (first-class functions), Self (prototypal inheritance), and Perl and Python (strings, arrays, and regular expressions).

JavaScript did not have exception handling until ECMAScript 3, which explains why the language so often automatically converts values and so often fails silently: it initially couldn’t throw exceptions.

On one hand, JavaScript has quirks and is missing quite a bit of functionality (block-scoped variables, modules, support for subclassing, etc.). On the other hand, it has several powerful features that allow you to work around these problems. In other languages, you learn language features. In JavaScript, you often learn patterns instead.

Given its influences, it is no surprise that JavaScript enables a programming style that is a mixture of functional programming (higher-order functions; built-in map, reduce, etc.) and object-oriented programming (objects, inheritance).

Syntax

This section explains basic syntactic principles of JavaScript.

An Overview of the Syntax

A few examples of syntax:

// Two slashes start single-line comments

var x; // declaring a variable

x = 3 + y; // assigning a value to the variable `x`

foo(x, y); // calling function `foo` with parameters `x` and `y`

obj.bar(3); // calling method `bar` of object `obj`

// A conditional statement

if (x === 0) { // Is `x` equal to zero?

x = 123;

}

// Defining function `baz` with parameters `a` and `b`

function baz(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

Note the two different uses of the equals sign:

- A single equals sign (=) is used to assign a value to a variable.

- A triple equals sign (===) is used to compare two values (see Equality Operators).

Statements Versus Expressions

To understand JavaScript’s syntax, you should know that it has two major syntactic categories: statements and expressions:

- Statements “do things.” A program is a sequence of statements. Here is an example of a statement, which declares (creates) a variable foo:

var foo;

- Expressions produce values. They are function arguments, the right side of an assignment, etc. Here’s an example of an expression:

3 * 7

The distinction between statements and expressions is best illustrated by the fact that JavaScript has two different ways to do if-then-else—either as a statement:

var x;

if (y >= 0) {

x = y;

} else {

x = -y;

}

or as an expression:

var x = y >= 0 ? y : -y;

You can use the latter as a function argument (but not the former):

myFunction(y >= 0 ? y : -y)

Finally, wherever JavaScript expects a statement, you can also use an expression; for example:

foo(7, 1);

The whole line is a statement (a so-called expression statement), but the function call foo(7, 1) is an expression.

Semicolons

Semicolons are optional in JavaScript. However, I recommend always including them, because otherwise JavaScript can guess wrong about the end of a statement. The details are explained in Automatic Semicolon Insertion.

Semicolons terminate statements, but not blocks. There is one case where you will see a semicolon after a block: a function expression is an expression that ends with a block. If such an expression comes last in a statement, it is followed by a semicolon:

// Pattern: var _ = ___;

var x = 3 * 7;

var f = function () { }; // function expr. inside var decl.

Comments

JavaScript has two kinds of comments: single-line comments and multiline comments. Single-line comments start with // and are terminated by the end of the line:

x++; // single-line comment

Multiline comments are delimited by /* and */:

/* This is

a multiline

comment.

*/

Variables and Assignment

Variables in JavaScript are declared before they are used:

var foo; // declare variable `foo`

Assignment

You can declare a variable and assign a value at the same time:

var foo = 6;

You can also assign a value to an existing variable:

foo = 4; // change variable `foo`

Compound Assignment Operators

There are compound assignment operators such as +=. The following two assignments are equivalent:

x += 1;

x = x + 1;

Identifiers and Variable Names

Identifiers are names that play various syntactic roles in JavaScript. For example, the name of a variable is an identifier. Identifiers are case sensitive.

Roughly, the first character of an identifier can be any Unicode letter, a dollar sign ($), or an underscore (_). Subsequent characters can additionally be any Unicode digit. Thus, the following are all legal identifiers:

arg0

_tmp

$elem

π

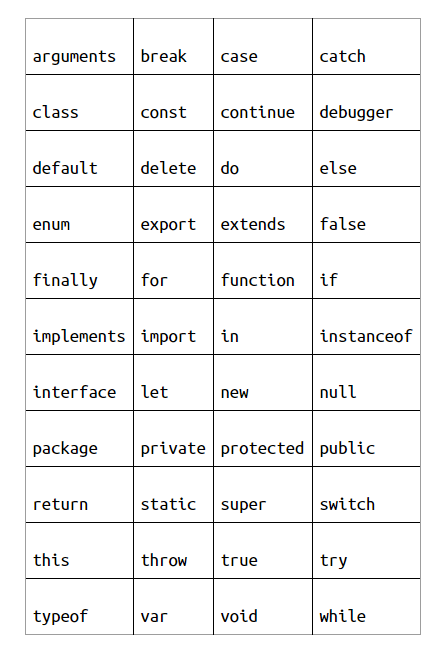

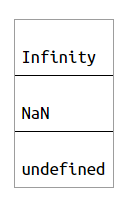

The following identifiers are reserved words—they are part of the syntax and can’t be used as variable names (including function names and parameter names):

The following three identifiers are not reserved words, but you should treat them as if they were:

Lastly, you should also stay away from the names of standard global variables. You can use them for local variables without breaking anything, but your code still becomes confusing.

Values

JavaScript has many values that we have come to expect from programming languages: booleans, numbers, strings, arrays, and so on. All values in JavaScript have properties.Each property has a key (or name) and a value. You can think of properties like fields of a record. You use the dot (.) operator to read a property:

value.propKey

For example, the string ‘abc’ has the property length:

> var str = 'abc';

> str.length

3

The preceding can also be written as:

> 'abc'.length

3

The dot operator is also used to assign a value to a property:

> var obj = {}; // empty object

> obj.foo = 123; // create property `foo`, set it to 123

123

> obj.foo

123

And you can use it to invoke methods:

> 'hello'.toUpperCase()

'HELLO'

In the preceding example, we have invoked the method toUpperCase() on the value ‘hello’.

Primitive Values Versus Objects

JavaScript makes a somewhat arbitrary distinction between values:

- The primitive values are booleans, numbers, strings, null, and undefined.

- All other values are objects. A major difference between the two is how they are compared; each object has a unique identity and is only (strictly) equal to itself:

> var obj1 = {}; // an empty object

> var obj2 = {}; // another empty object

> obj1 === obj2

false

> obj1 === obj1

true

In contrast, all primitive values encoding the same value are considered the same:

> var prim1 = 123;

> var prim2 = 123;

> prim1 === prim2

true

The next two sections explain primitive values and objects in more detail.

Primitive Values

The following are all of the primitive values (or primitives for short):

- Booleans: true, false (see Booleans)

- Numbers: 1736, 1.351 (see Numbers)

- Strings: ‘abc’, “abc” (see Strings)

- Two “nonvalues”: undefined, null (see undefined and null)

Primitives have the following characteristics:

Compared by value

The “content” is compared:

> 3 === 3

true

> 'abc' === 'abc'

true

###Always immutable Properties can’t be changed, added, or removed:

> var str = 'abc';

> str.length = 1; // try to change property `length`

> str.length // ⇒ no effect

3

> str.foo = 3; // try to create property `foo`

> str.foo // ⇒ no effect, unknown property

undefined

(Reading an unknown property always returns undefined.)

Objects

All nonprimitive values are objects. The most common kinds of objects are:

- Plain objects, which can be created by object literals (see Single Objects):

{

firstName: 'Jane',

lastName: 'Doe'

}

The preceding object has two properties: the value of property firstName is ‘Jane’ and the value of property lastName is ‘Doe’.

- Arrays, which can be created by array literals (see Arrays):

[ 'apple', 'banana', 'cherry' ]

The preceding array has three elements that can be accessed via numeric indices. For example, the index of ‘apple’ is 0.

- Regular expressions, which can be created by regular expression literals (see Regular Expressions):

/^a+b+$/

Objects have the following characteristics:

Compared by reference

Identities are compared; every value has its own identity:

> ({} === {}) // two different empty objects

false

> var obj1 = {};

> var obj2 = obj1;

> obj1 === obj2

true

Mutable by default

You can normally freely change, add, and remove properties (see Single Objects):

> var obj = {};

> obj.foo = 123; // add property `foo`

> obj.foo

123

undefined and null

Most programming languages have values denoting missing information. JavaScript has two such “nonvalues,” undefined and null:

- undefined means “no value.” Uninitialized variables are undefined:

> var foo;

> foo

undefined

Missing parameters are undefined:

> function f(x) { return x }

> f()

undefined

If you read a nonexistent property, you get undefined:

> var obj = {}; // empty object

> obj.foo

undefined

- null means “no object.” It is used as a nonvalue whenever an object is expected (parameters, last in a chain of objects, etc.).

WARNING

undefined and null have no properties, not even standard methods such as toString().

Checking for undefined or null

Functions normally allow you to indicate a missing value via either undefined or null. You can do the same via an explicit check:

if (x === undefined || x === null) {

...

}

You can also exploit the fact that both undefined and null are considered false:

if (!x) {

...

}

WARNING

false, 0, NaN, and “ are also considered false (see Truthy and Falsy).

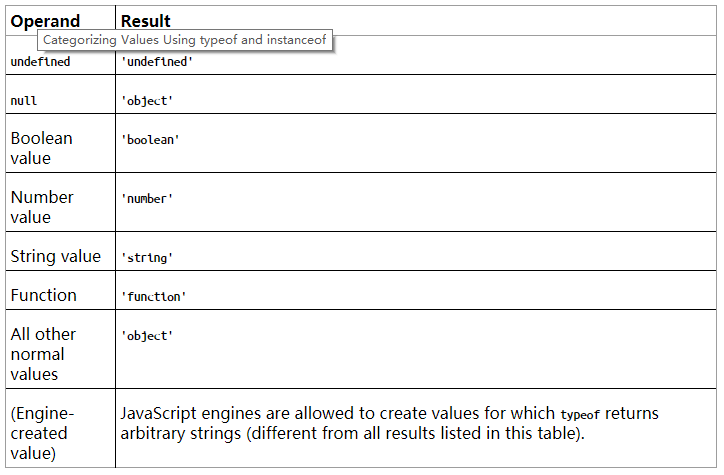

Categorizing Values Using typeof and instanceof

There are two operators for categorizing values: typeof is mainly used for primitive values, while instanceof is used for objects. typeof looks like this:

typeof value

It returns a string describing the “type” of value. Here are some examples:

> typeof true

'boolean'

> typeof 'abc'

'string'

> typeof {} // empty object literal

'object'

> typeof [] // empty array literal

'object'

The following table lists all results of typeof:

typeof null returning ‘object’ is a bug that can’t be fixed, because it would break existing code. It does not mean that null is an object.

instanceof looks like this:

value instanceof Constr

It returns true if value is an object that has been created by the constructor Constr (see Constructors: Factories for Objects). Here are some examples:

> var b = new Bar(); // object created by constructor Bar

> b instanceof Bar

true

> {} instanceof Object

true

> [] instanceof Array

true

> [] instanceof Object // Array is a subconstructor of Object

true

> undefined instanceof Object

false

> null instanceof Object

false

Booleans

The primitive boolean type comprises the values true and false. The following operators produce booleans:

- Binary logical operators: && (And), || (Or)

- Prefix logical operator: ! (Not)

- Comparison operators:Equality operators: ===, !==, ==, !=

- Ordering operators (for strings and numbers): >, >=, <, <=

Truthy and Falsy

Whenever JavaScript expects a boolean value (e.g., for the condition of an if statement), any value can be used. It will be interpreted as either true or false. The following values are interpreted as false:

- undefined, null

- Boolean: false

- Number: 0, NaN

- String: “

All other values (including all objects!) are considered true. Values interpreted as false are called falsy, and values interpreted as true are called truthy. Boolean(), called as a function, converts its parameter to a boolean. You can use it to test how a value is interpreted:

> Boolean(undefined)

false

> Boolean(0)

false

> Boolean(3)

true

> Boolean({}) // empty object

true

> Boolean([]) // empty array

true

Binary Logical Operators

Binary logical operators in JavaScript are short-circuiting. That is, if the first operand suffices for determining the result, the second operand is not evaluated. For example, in the following expressions, the function foo() is never called:

false && foo()

true || foo()

Furthermore, binary logical operators return either one of their operands—which may or may not be a boolean. A check for truthiness is used to determine which one:

And (&&)

If the first operand is falsy, return it. Otherwise, return the second operand:

> NaN && 'abc'

NaN

> 123 && 'abc'

'abc'

Or (||)

If the first operand is truthy, return it. Otherwise, return the second operand:

> 'abc' || 123

'abc'

> '' || 123

123

Equality Operators

JavaScript has two kinds of equality:

- Normal, or “lenient,” (in)equality: == and !=

- Strict (in)equality: === and !==

Normal equality considers (too) many values to be equal (the details are explained in Normal (Lenient) Equality (==, !=)), which can hide bugs. Therefore, always using strict equality is recommended.

Numbers

All numbers in JavaScript are floating-point:

> 1 === 1.0

true

Special numbers include the following:

NaN (“not a number”) An error value:

> Number('xyz') // 'xyz' can’t be converted to a number

NaN

Infinity Also mostly an error value:

> 3 / 0

Infinity

> Math.pow(2, 1024) // number too large

Infinity

Infinity is larger than any other number (except NaN). Similarly, -Infinity is smaller than any other number (except NaN). That makes these numbers useful as default values (e.g., when you are looking for a minimum or a maximum).

Operators

JavaScript has the following arithmetic operators (see Arithmetic Operators):

- Addition: number1 + number2

- Subtraction: number1 - number2

- Multiplication: number1 * number2

- Division: number1 / number2

- Remainder: number1 % number2

- Increment: ++variable, variable++

- Decrement: –variable, variable–

- Negate: -value

- Convert to number: +value

The global object Math (see Math) provides more arithmetic operations, via functions.

JavaScript also has operators for bitwise operations (e.g., bitwise And; see Bitwise Operators).

Strings

Strings can be created directly via string literals. Those literals are delimited by single or double quotes. The backslash () escapes characters and produces a few control characters. Here are some examples:

'abc'

"abc"

'Did she say "Hello"?'

"Did she say \"Hello\"?"

'That\'s nice!'

"That's nice!"

'Line 1\nLine 2' // newline

'Backlash: \\'

Single characters are accessed via square brackets:

> var str = 'abc';

> str[1]

'b'

The property length counts the number of characters in the string:

> 'abc'.length

3

Like all primitives, strings are immutable; you need to create a new string if you want to change an existing one.

String Operators

Strings are concatenated via the plus (+) operator, which converts the other operand to a string if one of the operands is a string:

> var messageCount = 3;

> 'You have ' + messageCount + ' messages'

'You have 3 messages'

To concatenate strings in multiple steps, use the += operator:

> var str = '';

> str += 'Multiple ';

> str += 'pieces ';

> str += 'are concatenated.';

> str

'Multiple pieces are concatenated.'

String Methods

Strings have many useful methods (see String Prototype Methods). Here are some examples:

> 'abc'.slice(1) // copy a substring

'bc'

> 'abc'.slice(1, 2)

'b'

> '\t xyz '.trim() // trim whitespace

'xyz'

> 'mjölnir'.toUpperCase()

'MJÖLNIR'

> 'abc'.indexOf('b') // find a string

1

> 'abc'.indexOf('x')

-1

Statements

Conditionals and loops in JavaScript are introduced in the following sections.

Conditionals

The if statement has a then clause and an optional else clause that are executed depending on a boolean condition:

if (myvar === 0) {

// then

}

if (myvar === 0) {

// then

} else {

// else

}

if (myvar === 0) {

// then

} else if (myvar === 1) {

// else-if

} else if (myvar === 2) {

// else-if

} else {

// else

}

I recommend always using braces (they denote blocks of zero or more statements). But you don’t have to do so if a clause is only a single statement (the same holds for the control flow statements for and while):

if (x < 0) return -x;

The following is a switch statement. The value of fruit decides which case is executed:

switch (fruit) {

case 'banana':

// ...

break;

case 'apple':

// ...

break;

default: // all other cases

// ...

}

The “operand” after case can be any expression; it is compared via === with the parameter of switch.

Loops

The for loop has the following format:

for (⟦«init»⟧; ⟦«condition»⟧; ⟦«post_iteration»⟧)

«statement»

init is executed at the beginning of the loop. condition is checked before each loop iteration; if it becomes false, then the loop is terminated. post_iteration is executed after each loop iteration.

This example prints all elements of the array arr on the console:

for (var i=0; i < arr.length; i++) {

console.log(arr[i]);

}

The while loop continues looping over its body while its condition holds:

// Same as for loop above:

var i = 0;

while (i < arr.length) {

console.log(arr[i]);

i++;

}

The do-while loop continues looping over its body while its condition holds. As the condition follows the body, the body is always executed at least once:

do {

// ...

} while (condition);

In all loops:

- break leaves the loop.

- continue starts a new loop iteration.

Functions

One way of defining a function is via a function declaration:

function add(param1, param2) {

return param1 + param2;

}

The preceding code defines a function, add, that has two parameters, param1 and param2, and returns the sum of both parameters. This is how you call that function:

> add(6, 1)

7

> add('a', 'b')

'ab'

Another way of defining add() is by assigning a function expression to a variable add:

var add = function (param1, param2) {

return param1 + param2;

};

A function expression produces a value and can thus be used to directly pass functions as arguments to other functions:

someOtherFunction(function (p1, p2) { ... });

Function Declarations Are Hoisted

Function declarations are hoisted—moved in their entirety to the beginning of the current scope. That allows you to refer to functions that are declared later:

function foo() {

bar(); // OK, bar is hoisted

function bar() {

...

}

}

Note that while var declarations are also hoisted (see Variables Are Hoisted), assignments performed by them are not:

function foo() {

bar(); // Not OK, bar is still undefined

var bar = function () {

// ...

};

}

The Special Variable arguments

You can call any function in JavaScript with an arbitrary amount of arguments; the language will never complain. It will, however, make all parameters available via the special variable arguments. arguments looks like an array, but has none of the array methods:

> function f() { return arguments }

> var args = f('a', 'b', 'c');

> args.length

3

> args[0] // read element at index 0

'a'

Too Many or Too Few Arguments

Let’s use the following function to explore how too many or too few parameters are handled in JavaScript (the function toArray() is shown in Converting arguments to an Array):

function f(x, y) {

console.log(x, y);

return toArray(arguments);

}

Additional parameters will be ignored (except by arguments):

> f('a', 'b', 'c')

a b

[ 'a', 'b', 'c' ]

Missing parameters will get the value undefined:

> f('a')

a undefined

[ 'a' ]

> f()

undefined undefined

[]

Optional Parameters

The following is a common pattern for assigning default values to parameters:

function pair(x, y) {

x = x || 0; // (1)

y = y || 0;

return [ x, y ];

}

In line (1), the || operator returns x if it is truthy (not null, undefined, etc.). Otherwise, it returns the second operand:

> pair()

[ 0, 0 ]

> pair(3)

[ 3, 0 ]

> pair(3, 5)

[ 3, 5 ]

Enforcing an Arity

If you want to enforce an arity (a specific number of parameters), you can check arguments.length:

function pair(x, y) {

if (arguments.length !== 2) {

throw new Error('Need exactly 2 arguments');

}

...

}

Converting arguments to an Array

arguments is not an array, it is only array-like (see Array-Like Objects and Generic Methods). It has a property length, and you can access its elements via indices in square brackets. You cannot, however, remove elements or invoke any of the array methods on it. Thus, you sometimes need to convert arguments to an array, which is what the following function does (it is explained in Array-Like Objects and Generic Methods):

function toArray(arrayLikeObject) {

return Array.prototype.slice.call(arrayLikeObject);

}

Exception Handling

The most common way to handle exceptions (see Chapter 14) is as follows:

function getPerson(id) {

if (id < 0) {

throw new Error('ID must not be negative: '+id);

}

return { id: id }; // normally: retrieved from database

}

function getPersons(ids) {

var result = [];

ids.forEach(function (id) {

try {

var person = getPerson(id);

result.push(person);

} catch (exception) {

console.log(exception);

}

});

return result;

}

The try clause surrounds critical code, and the catch clause is executed if an exception is thrown inside the try clause. Using the preceding code:

> getPersons([2, -5, 137])

[Error: ID must not be negative: -5]

[ { id: 2 }, { id: 137 } ]

Strict Mode

Strict mode (see Strict Mode) enables more warnings and makes JavaScript a cleaner language (nonstrict mode is sometimes called “sloppy mode”). To switch it on, type the following line first in a JavaScript file or a

- General agreement (Lex)

- How to add long lines at the bottom of the drawing line library

- How does strategic review serve as a benchmark for returns?

- 4.5 C++ Language Quick Start

- 4.4 How to implement strategies in Python language

- What is the number of slippage points?

- GateIO futures used for aggregate

- 4.3 Getting started with the Python language

- 4.2 How to implement strategic trading in JavaScript language

- Can you tell me how to build a native retrieval system for python3?

- 3.5 Visual Programming language implementation of trading strategies

- Please ask GetTicker why the data is empty.

- 3.4 Visual programming quick start

- 3.3 How to implement strategies in M language

- How do you set up leveraged trading?

- How do you add the EOS futures trading pair to OKEX?

- If you want to add a new exchange, please do not hesitate to add a new exchange.

- Can robots that have already been started, modified strategies in the run, be effective?

- 3.2 Getting started with the M language

- Problems with writing API interface programs for bitmex market price cap stops and triggered post-placement