The most profitable economist, writing papers and leading economist, Tom Maynard Keynes

Author: Inventors quantify - small dreams, Created: 2017-01-05 10:59:15, Updated: 2017-01-05 14:09:18The most profitable economist, who writes papers and is the leader, is Jean-Ménard Keynes.

The influence of Maynard Keynes probably extends far beyond the purely economic sphere, and whether it is political science or sociological logic, Keynes has undoubtedly become a symbolic figure.

- ### by Maynard Keynes

In the last issue we announced that this issue will be about Maynard Keynes. The influence of this person has probably gone completely beyond the purely economic category, whether it is political science or sociological logic. Keynes has undoubtedly become a symbolic figure long ago. For example, if you discuss Keynes and Hayek on Weibo, you will immediately get different reviews, basically in line with the style of commentary below Cao Yunqing's Weibo.

Compared to the American countryside where Knight defined the concept of economic risk in the previous issue, Keynes was a typical English aristocrat, whose ancestors were the conquerors who landed in England from Normandy with William, and when it comes to the return of the British and American troops from Normandy to Europe during World War II, history is still a cycle. Keynes was born on what we call the upper-elite route, graduated from Eton Public Schools to Cambridge University, his teachers were Marshall, his colleagues were Saul and Wittgenstein, and his first job after graduation was at the British Treasury, if there was no difference in language, he could completely change his surname.

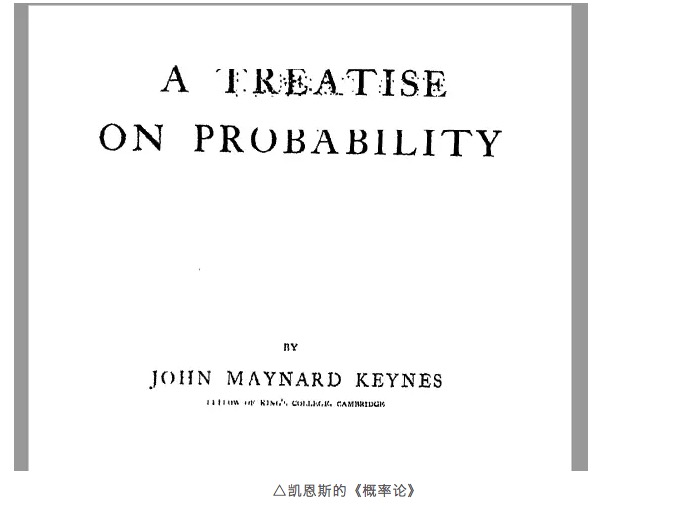

Dissatisfied with British foreign policy, Keynes resigned as chief negotiator in the Treasury and returned to teaching at Cambridge University. In fact, contrary to what most people think of Keynes as a simple economic thinker, Keynes had a better mathematical foundation than his contemporaries, such as the Ramsey model, one of the foundations of contemporary macroeconomics. In 1921, Keynes published a brilliant work on probability theory, which was not, of course, a simple textbook, but rather a more in-depth study of the meaning and application of probability.

Unlike everyone else we have written about before, Keynes has a disdain for the axiom of majority and homogeneity, and he believes that the use of historical frequencies to judge the probability of future events is probably only appropriate in nature and not in the field of sociology, which is full of human curiosity. Because he believes that there is an objective probability of future events, and that objective probabilities do not change with changes in human consciousness, but that our knowledge of the precise probabilities is insufficient, we cannot obtain accurate estimates, and that such estimates are not the reason we insist on judging the correctness of the particulars.

Keynes believed that the probabilities we use on a daily basis are more of a subjective concept, reflecting our confidence in the future, and are only a component of information about future events. From an economic point of view, he assumed that all rational people (i.e. rational people) would recognize the probability of an outcome in time and therefore have the same confidence in the future. This assumption was very economical, but it was not realistic in practice, so Keynes finally made concessions, saying that people's understanding of probability and risk depends on each person's own judgment.

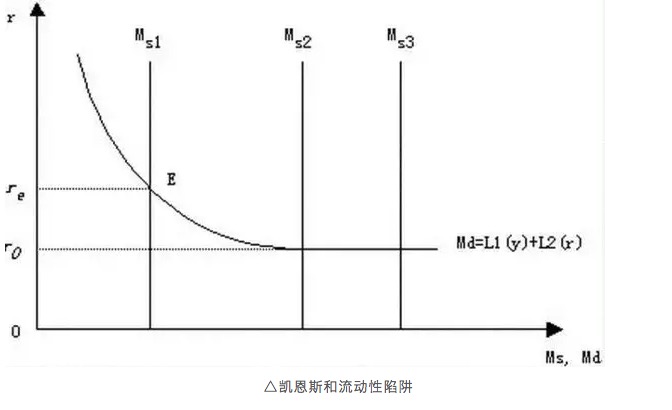

Keynes's study of economics revolves around uncertainties, such as the uncertainty of household savings and consumption depending on the amount and time of use in different economic environments, and the uncertainty of how profits are generated by corporate capital investment. He disliked the assumptions in classical economics, because in reality all decisions we make are irreversible, meaning that the stable environment that classical economics assumes is unavailable if the economy is often in a situation of hyper-growth or stagnation.

Regardless of Keynes's ultimate solution to the apparent loophole, the emphasis on fluidity preferences in Keynesian systems of theory is actually a reflection of the desire of people in the real world to lock in the future in different ways. In other words, in Keynes' view, uncertainty and the risks of uncertainty (which Keynes does not distinguish as sharply as Knight does between risk and uncertainty) are the dominant and central ones in the real world.

We can't control the outcome of the next dice, we can't control the correctness of the next prediction, but things will eventually return to a stable normal that exists in the afterlife. But, as Keynes said, it all exists only in mathematical theory and some natural phenomena, and for human society, probability seems to be a tool to be used, not a truth. This means that our decisions in the face of future uncertainty are important, and a fundamental force for shaping the future and the world. Keynes's economic stimulus plan and his initial £10 million stake in the stock market prove that, after all, the human market is a passive receiver, not a market built by humans.

This gives us a glimpse into the world of hedging and risk management, but where the methodology actually comes from may have to wait until the next issue of Gambling Theory to explain.

Translated from Chinese Quantitative Investment Society

- Python -- numpy matrix operations

- Algorithmic trading strategies

- Martinel's tactics, his single-handed gamble on fate?

- JSLint detects the syntax of JavaScript

- How partial equity impacts the average price of holdings

- Bitcoin exchange network error GetOrders: parameter error

- The template of the listing system triggers the design outline of ten items

- The technical gist of the shark system trading rules

- Template 3.0: Draw line class library

- Peak and slope

- Template 3.2: Digital currency trading class library (integrated Cash, futures support OKCoin futures/BitVC)

- I'm sorry, but Gauss did a small job.

- A Brief History of Risk (IV) Von Mover and the Curve of the Gods

- A short history of risk (5) Bayes, a man who lives only in his textbooks

- A brilliant explanation for the alternative to stop loss

- OkCoin China API error code requested

- 2.12 _D (()) Function and Timestamp

- python: Please be careful in these places.

- A synergistic understanding of intuition

- The hidden Markov model