Poke for bargain high-frequency trading strategy

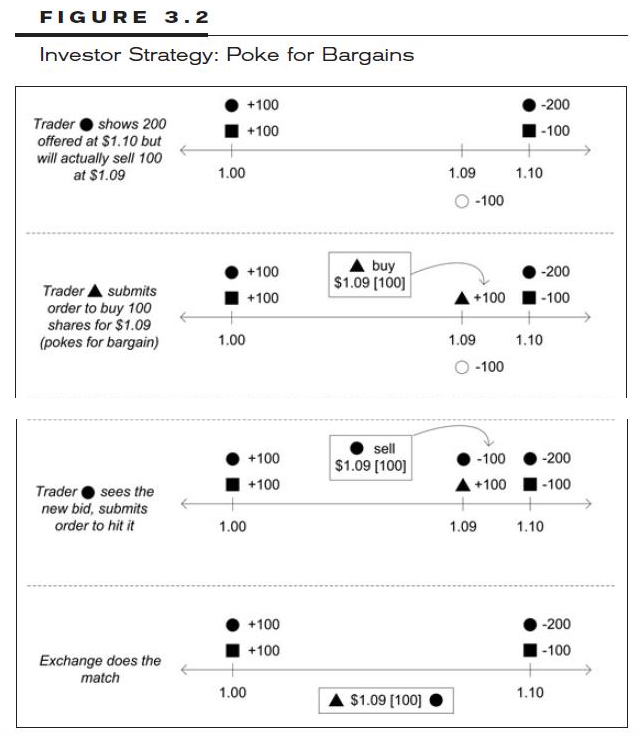

Author: Zero, Created: 2015-06-07 08:24:43, Updated: 2015-06-09 11:23:41Before introducing this strategy, we first categorized the people involved in trading in the market into two types, investors and market makers. Investors are typically large investment firms such as overseas trust fund managers, life insurance investment departments, sovereign wealth fund managers, etc. They buy stocks in the market and earn a profit on the increase in the stock price. They usually use single market orders or single limit order entries close to the current market price. If they use single market orders, they are using liquidity buffers. Market makers are usually securities brokers or specialized market makers, who are responsible for listing a number of bid and ask quotes in the market, and their main purpose is not to profit from the rise (or fall) of the price after the stock is traded.\(1.00 payment and \)If she's selling a 1.10 bill, then her goal is to make money.\(1.10 and \)This is the middle of 1.00.\(0.1 difference in price.A profit of 0.1 is the reward that the market maker gets for creating liquidity bubbles. In the real world of trading, a market maker (or so-called liquidity maker) may put the bid and ask order a little further away from the price at which she is actually willing to trade. For example, today a market maker is willing to put the bid and ask order a little further away from the price at which she is actually willing to trade.\(1.01 bought a stock, but the bill she hung up, will hang more than \)So let's say that we have a little bit less than 1.01.\($1.00 payment. So if there is a seller who is in a hurry or unwilling to wait, they can eat it directly from the market price list\)If the market maker buys more than she expected, then the market maker buys more than she expected.\(1.01) is also cheaper.The stock price is 1.00). So, if this market maker is willing to use\(1.09 sells a stock, but she may be hanging out\)She is also the only woman in the world who has a 1.10 bill to attract a sexual impulse to buy at the market price.\(1.10) than she expected.The price is a little higher. Let's say I'm an investor now, and I know that market makers will have this pattern of behavior, so I can develop a corresponding strategy called poke for bargains.\(1.00 x \)1.10? Then I can hang it up.I'll pay $1.09 and see if the market maker eats me.The price of 1.09 ⋅ if there is, that's the price I bought it for.If I were to buy a new car, I would pay $1.09, which is more than I would have paid with a list price.I'm going to have to pay $0.01 for the 1.10) and my purchase cost will be a little bit lower.

The next step is that if I want to buy this stock, I don't hang it up.\(1.09 for the bill, but try hanging it first\)I'm going to try to get a 1.05 bill and see if someone jumps out and eats my bill, and if they don't, I'm going to try to get this one.\(1.05 payment cancelled and then hung up\)1.06 payment, see if it gets eaten, if it hasn't, cancel.\(1.06 payment, replaced by hanging \)I'll pay $1.07 and then continue the same process until my bill is eaten.\(1.06 or \)I'm going to trade at $1.10 if the worst-case scenario happens. And that's not going to be any less than what I bought at the market price. The above actions are not entered manually from the keyboard in front of the computer, but are all executed by a program that has already been written. The speed of execution of these transactions is usually completed in a matter of seconds.

- Some tips for re-testing the wrong packaging

- TypeError: Cannot access member 'GetRecords' of undefined at

:1:-1 Where is the problem? - On the strategy of single platform balancing

- Why choose to trade strategically on the FMZ Quantitative Trading Platform (BotVS)

- The strategy of making money could also be a coin.

- Inventors quantify the path of automated trading

- The Law of Grid Trading

- I've created a forum, use it for a while.

- Join the Makers in high-frequency trading strategy

- Reserve orders and iceberg orders for high-frequency trading strategies

- Improvements and advantages of multi-platform hedge stability swap V2.7

- About being sucked in

- Single-point sniper with high-frequency stacking automatic counter-hand unlocking algorithm

- Penny Jump for high-frequency trading strategy

- Take out slow movers of high frequency trading strategy

- Push the Elephant in high-frequency trading strategy

- Scratch for the Rebate high frequency trading strategy